There is no disease more infamous or feared by gardeners than late blight. Watching your thriving tomato or potato plants suddenly develop dark, watery lesions and collapse in a matter of days is a truly devastating experience.

This destructive force, responsible for historical famines, can turn a promising harvest into a complete loss with shocking speed. But you are not powerless. This guide will give you the knowledge you need to identify its first signs, understand its causes, and take proven steps to protect your plants.

What is late blight & why is it a serious threat to plants?

Late blight is an extremely destructive plant disease caused by the water mold, or oomycete, Phytophthora infestans. It is not a true fungus but behaves like one, spreading rapidly and killing plant tissue.

It is a serious threat due to its historical significance and its massive agricultural impact. Late blight is the disease responsible for the Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s, which led to the death of over a million people and the emigration of millions more.

Today, it remains a global threat. The International Potato Center (CIP) estimated that late blight causes a global economic loss of approximately $2.75 billion in developing countries annually, based on an average production loss of 15%. In the United States alone, the economic impact was estimated to be around $210 million in a single year. For both home gardeners and commercial farmers, an outbreak can mean total crop failure if not managed.

Which plants are most vulnerable to late blight?

The primary hosts of late blight are potatoes and tomatoes, as they are both members of the nightshade family (Solanaceae). However, the pathogen can also infect a few other related plants, including:

- Petunias (under ideal greenhouse conditions)

- Hairy nightshade (a common weed that can help spread the disease)

The impact varies greatly by scale. In a home garden, a late blight outbreak can mean the heartbreaking loss of a season’s worth of homegrown produce. For commercial farmers, the same outbreak can be financially catastrophic, destroying thousands of acres and threatening their livelihood.

How can you identify the symptoms of late blight?

Late blight progresses very quickly, so recognizing the earliest symptoms is critical. The disease can affect all parts of the plant.

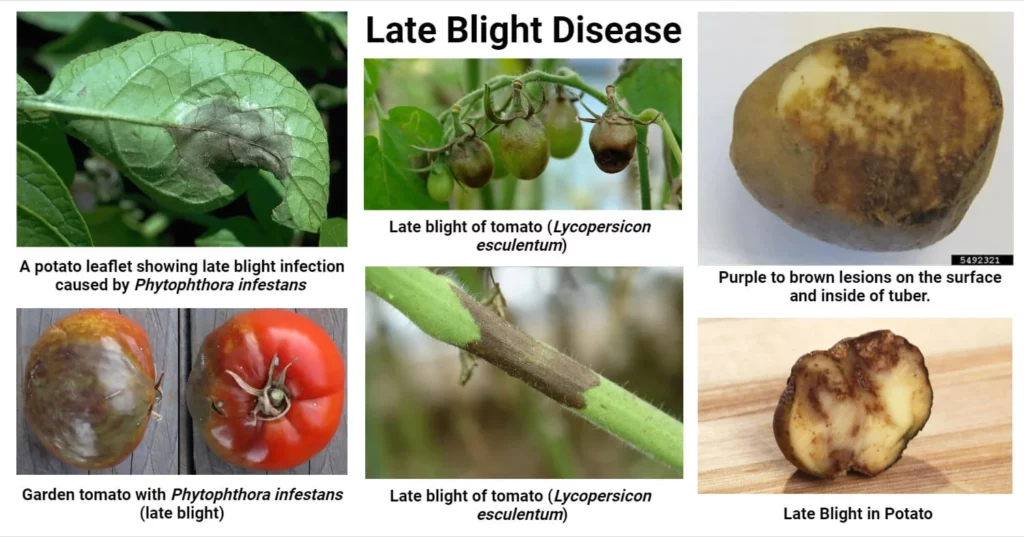

Look for large, dark brown or black, water-soaked spots (lesions) on the leaves, often with a pale green or gray edge. Unlike other diseases, these spots are not confined to the major leaf veins. The infection can move through the stems, which develop firm, dark brown lesions. In just a few days of cool, wet weather, entire plants can wilt and turn brown as if they were hit by a frost.

To confirm an infection, look for these key symptoms on different parts of the plant:

- White Mold: The most definitive sign is a fuzzy, white, powdery growth that appears on the underside of infected leaves or on the lesions themselves, especially in high humidity.

- Tomato Fruit: Infected tomatoes develop large, firm, dark brown, circular spots that may become mushy as secondary bacteria invade.

- Potato Tubers: On potatoes, the skin can show patches of brown to purple discoloration. Underneath the skin, the tuber flesh will have a reddish-brown, grainy decay that can lead to rot during storage.

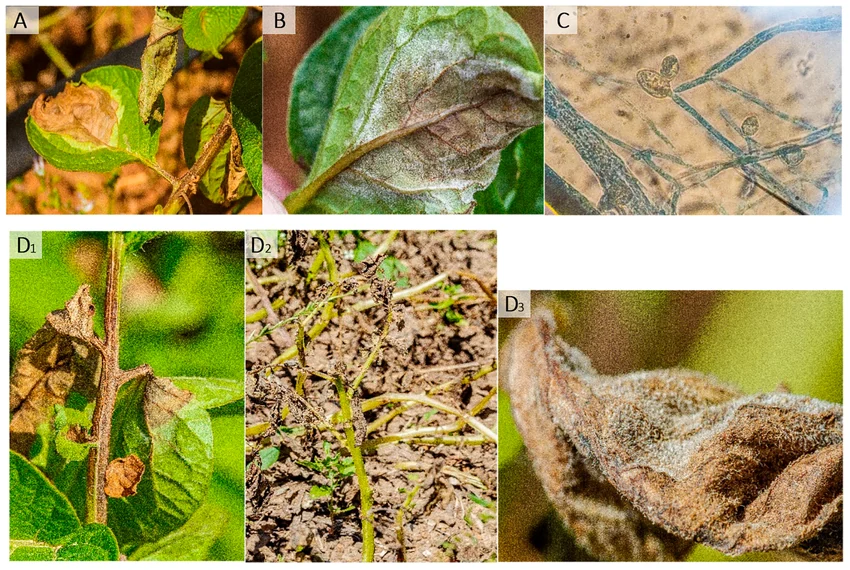

Typical late blight symptoms include oily, dark spots with pale green edges on the upper leaf surface (A) and white downy growth underneath (B–C), caused by pathogen sporangia. Stems and petioles may also be infected (D1). In advanced stages, leaves and even the whole plant can be blighted (D2–D3). Photograph: A. Taoutaou.

How does late blight spread & what conditions favor it?

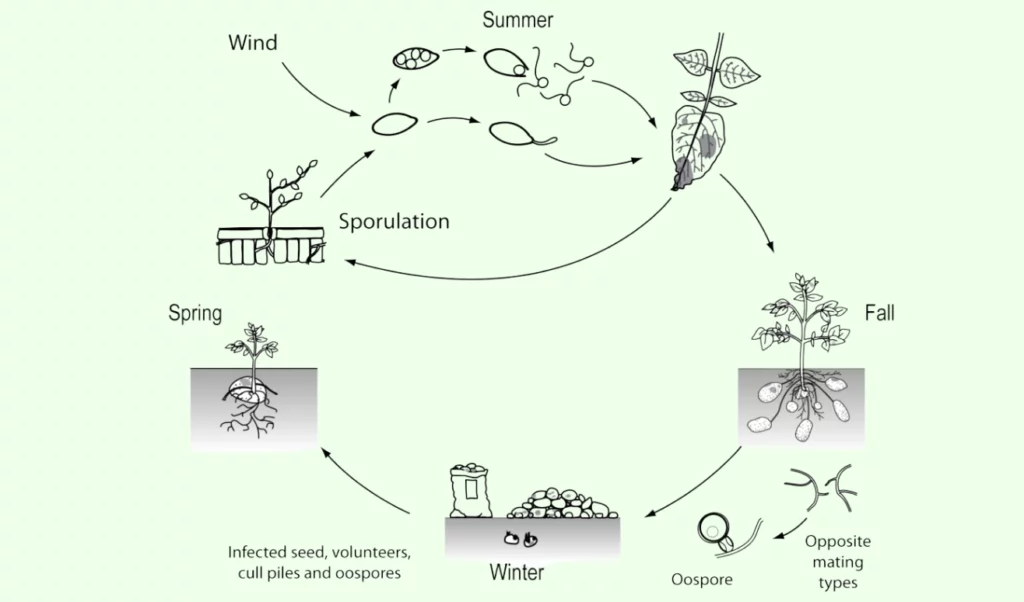

Late blight is a master of survival and spread, which is why it is so feared. The pathogen typically overwinters in infected potato tubers that were left in the soil or in cull piles (piles of discarded potatoes). It can also be introduced to a new area on infected tomato transplants or certified seed potatoes.

When conditions are right, the overwintering pathogen produces spores. These spores are incredibly lightweight and are easily dispersed by wind and rain splash, traveling for miles to infect new plants. The disease thrives in cool, damp conditions, with high humidity (above 90%) and temperatures between 15-21°C (60-70°F).

Under these ideal conditions, the disease can complete its entire life cycle, from infection to producing new spores, in as little as five days, leading to an explosive outbreak. Just one infected plant is enough to start a severe epidemic.

Life cycle of potato late blight

What are effective ways to prevent late blight in your garden or farm?

- Use certified disease-free seed potatoes and healthy transplants to avoid introducing the pathogen to your garden.

- Choose resistant varieties. Many modern potato and tomato varieties are bred for resistance to late blight.

- Practice good sanitation. Destroy all “volunteer” potato and tomato plants that sprout from the previous year. Do not leave cull piles exposed; burn, bury, or compost them properly.

- Ensure good air circulation by spacing plants properly and using trellises to keep vines off the ground.

- Water at the base of the plant using soaker hoses or drip irrigation. Keeping foliage dry is critical. If you must water overhead, do it early in the day so the leaves can dry completely.

- Rotate your crops. Avoid planting tomatoes and potatoes in the same spot for at least two to three years.

- Monitor plants regularly, especially during cool, wet weather. Remove and destroy any suspicious-looking plants immediately.

Conclusion

In the end, while late blight is one of the most formidable challenges a gardener can face, a proactive and vigilant approach can make all the difference. Understanding the conditions it loves and practicing smart prevention are your best weapons in this fight.

For a modern ally, the Planteyes app is an excellent tool for helping you identify early disease symptoms from a photo. You can also use its in-app chat feature to connect with an expert for personalized advice, giving you the confidence to act quickly. Download it today and give your plants the best possible defense against this devastating disease.

FAQs

Can late blight survive in the soil over winter?

Yes, the pathogen overwinters in infected potato tubers left in the soil or in unprotected cull piles. It needs living tissue to survive, so it won’t persist on tomato cages or dead plant matter (unless resilient resting spores are produced, which is becoming more common).

How is late blight different from early blight?

Late blight causes large, watery, dark lesions that are not confined by leaf veins and often have a white, fuzzy mold on the underside. Early blight typically produces smaller, dark spots with distinct, concentric “bull’s-eye” rings that are often contained within the leaf veins.

Is late blight harmful to humans if infected produce is eaten?

The pathogen Phytophthora infestans is not harmful to humans. However, the blighted parts of the fruit or tuber will taste bad, and the rot can be followed by secondary bacteria and molds that could be harmful, so it’s best to discard any affected produce.

How long does it take for late blight to destroy a plant?

Under ideal cool, wet conditions, late blight can destroy a plant or an entire crop with incredible speed, sometimes within 7-10 days of the first symptoms appearing.

Is there an app that can help identify late blight in plants?

Yes, modern plant disease identification apps like Planteyes are designed to analyze photos of your plants to help you recognize the characteristic symptoms of late blight, enabling you to take immediate action.