Barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) is one of the most destructive cereal viruses in the world, stealing the vitality from barley, wheat, and oats on a massive scale. It rarely turns up in home gardens, but for farmers, it’s a relentless threat that can wipe out harvests and livelihoods. This article walks you through the story of BYDV: what it is, how it spreads, the tell‑tale signs to look for, and the tools and strategies farmers can use to fight back, so the next barley field you see can stay green and full of life.

The Global Context of Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus (BYDV)

BYDV was formally identified in 1951 in California barley fields, exhibiting yellowing and stunting; however, herbarium evidence suggests it was present in grasses decades earlier. From those early findings, the virus spread with trade and farming, eventually affecting cereals worldwide.

- First records: Initially found in barley, later seen in wheat, oats, and other grains.

- Origins and spread: Likely began in the U.S., moving globally via trade and agriculture.

- Impact: Billions in yield losses each year; early infection can cut crops by up to half.

- Hotspots: Cool, temperate regions, such as Northern Europe, parts of the U.S., and Australia, are the most brutal hit.

- Hosts: Infects 150+ grass species and persists in wild grasses, carried by aphids between seasons.

This condensed history, impact, and reach explain why BYDV remains one of agriculture’s most serious viral threats.

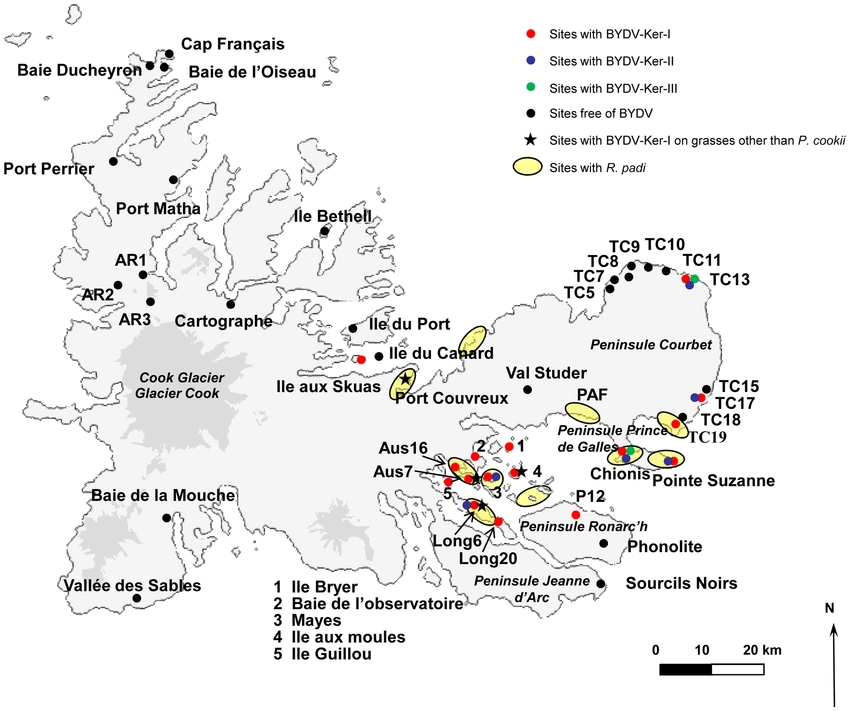

Map of BYDV strain distribution sites

Causes and How Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus (BYDV) Spreads

Barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) doesn’t appear on its own. It depends on aphids to move from plant to plant. Understanding both the triggers and the pathways helps farmers stop it before it spreads.

Key Causes of Infection

- Aphid feeding: BYDV is transmitted only when aphids feed on plants, drawing sap and passing the virus into the plant’s phloem.

- Reservoir plants: Perennial grasses, weeds, and volunteer cereals carry the virus between seasons, giving aphids a constant source.

- Seasonal risks: Mild winters and wet springs keep aphids active and abundant, raising infection chances. Early autumn sowing often overlaps with peak aphid flights, creating a perfect storm.

How It Spreads

First, more than 20 aphid species — including the bird cherry–oat aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi) and the grain aphid (Sitobion avenae) — can acquire BYDV after feeding on an infected plant for just 30 minutes to 12 hours.

Second, once they pick up the virus, they remain lifelong carriers, ready to infect new plants with every bite.

Third, winged aphids fly in from surrounding grasses and pastures to initiate new infection sites, while their wingless offspring crawl between plants, steadily expanding the outbreak.

Finally, BYDV is not carried in seed or soil and isn’t spread by machinery — it survives only in living plant tissue, making aphids the single, essential bridge for transmission.

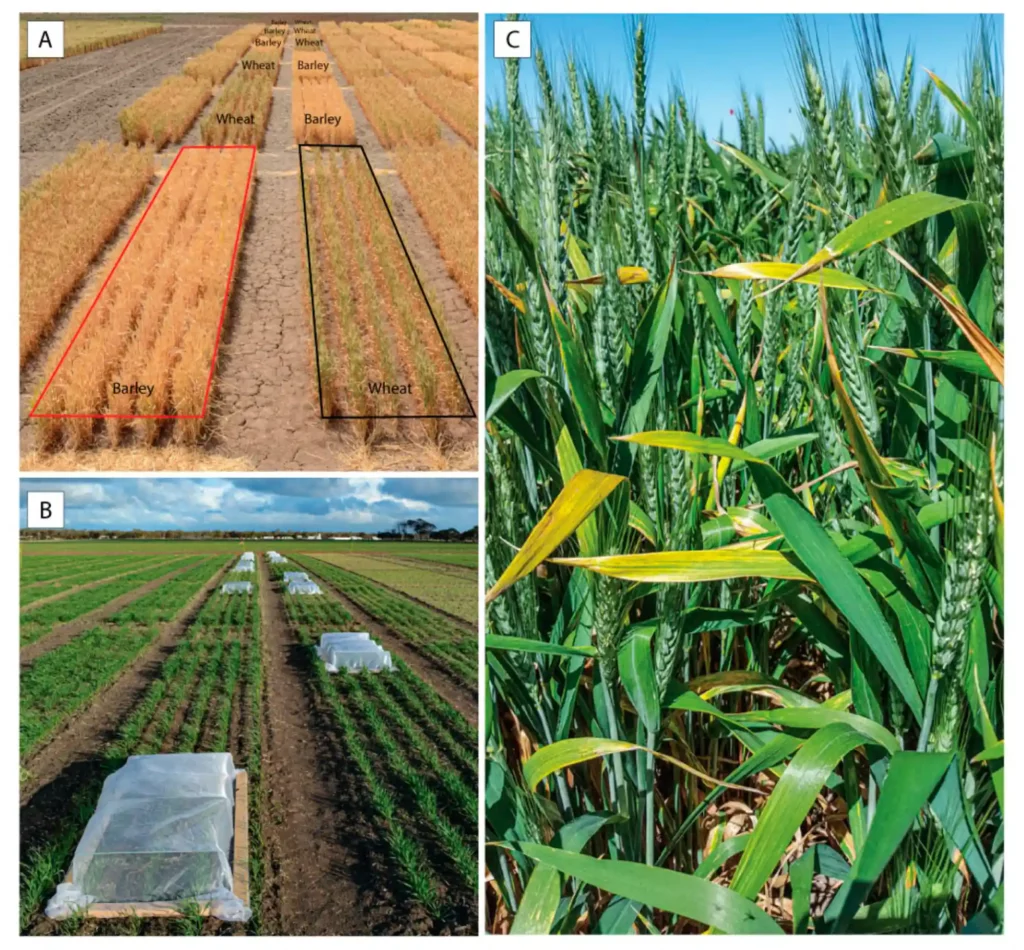

This image shows BYDV spread in action: field plots with infection patches (A), mesh-covered areas for aphid control (B), and wheat leaves showing yellowing from aphid‑borne infection (C)

Signs and Symptoms of BYDV Farmers Should Watch For

#1 Leaf Discoloration

Yellowing or reddening of leaf tips and edges is the most visible sign, often appearing 2–3 weeks after aphid infection. Barley tends to show bright yellow tips, wheat turns pale yellow or red, and oats shift from orange‑red to purple.

#2 Plant Stunting and Growth Issues

Infected plants are dwarfed, produce fewer tillers, and develop stiff upright leaves with weak roots. This leads to delayed heading and late ripening.

#3 Foliage Damage Patterns

Leaves may develop serrated edges, blotches that merge into larger areas of discoloration, and even secondary bacterial streaks.

#4 Yield-Related Clues

Severe infections cause smaller heads, shriveled or sterile grains, and reduced biomass. Some plants may fail to head or emerge fully.

#5 Field-Level Signs

Symptoms often appear in circular patches or along field edges, where aphids first land, and slowly spread outward. They don’t form a mosaic pattern like some other viruses.

Strategies to Control Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus (BYDV)

| Category | Key Actions | Notes |

| Cultural Practices | – Delay autumn sowing of winter cereals until after peak aphid flights. – Remove volunteer cereals and grassy weeds 4–5 weeks before planting. – Rotate crops and avoid back‑to‑back cereals. | Limits aphid exposure and removes virus reservoirs. |

| Genetic Resistance | – Choose BYDV‑tolerant cultivars (e.g., Amistar barley, Wolverine wheat). – Mix different varieties to spread risk. | Reduces symptoms and yield losses, even in plants infected with the disease. |

| Chemical Controls | – Use seed treatments (e.g., imidacloprid, thiamethoxam) for early protection. – Apply pyrethroid sprays at the 2–3 leaf stage based on aphid scouting. | Should be timed carefully; overuse can harm beneficial insects and lead to resistance. |

| Monitoring & IPM | – Scout fields with traps and apps like Planteyes. – Encourage natural enemies like ladybugs and parasitic wasps. – Combine cultural, genetic, and chemical measures. | Integrated approaches offer the best long‑term control while staying sustainable. |

Conclusion

Barley yellow dwarf virus poses a significant threat to cereal production worldwide, but farmers can counteract this threat with informed strategies. Combining aphid control, resistant varieties, and smart field management reduces losses and protects yields for the long term — and with tools like the Planteyes app, farmers can quickly identify BYDV symptoms in the field and take action before the damage spreads.

FAQs

What crops are most affected by barley yellow dwarf virus?

Barley, wheat, and oats are the most heavily damaged, with losses reaching up to half the yield in severe outbreaks. Other cereals like rye and triticale, and even over 150 grass species, can also host the virus.

How do aphids spread BYDV between fields?

Aphids pick up the virus while feeding on an infected plant—sometimes in as little as 30 minutes—and then carry it for life, injecting it into new plants with each bite.

Can BYDV be confused with nutrient deficiencies in plants?

Yes. Yellow or red leaf tips can look like nitrogen or phosphorus problems, but BYDV usually starts on younger leaves and shows up in irregular patches instead of even discoloration.

Is there an app that helps farmers identify BYDV in the field?

Yes. The Planteyes app can help spot BYDV symptoms quickly, compare them with look‑alike issues, and guide next steps for treatment.